A Salty ‘Peanut’ Asteroid Could Reveal Where Earth Got Its Water

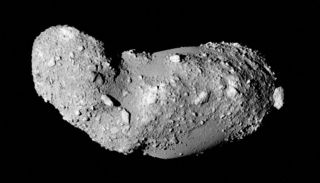

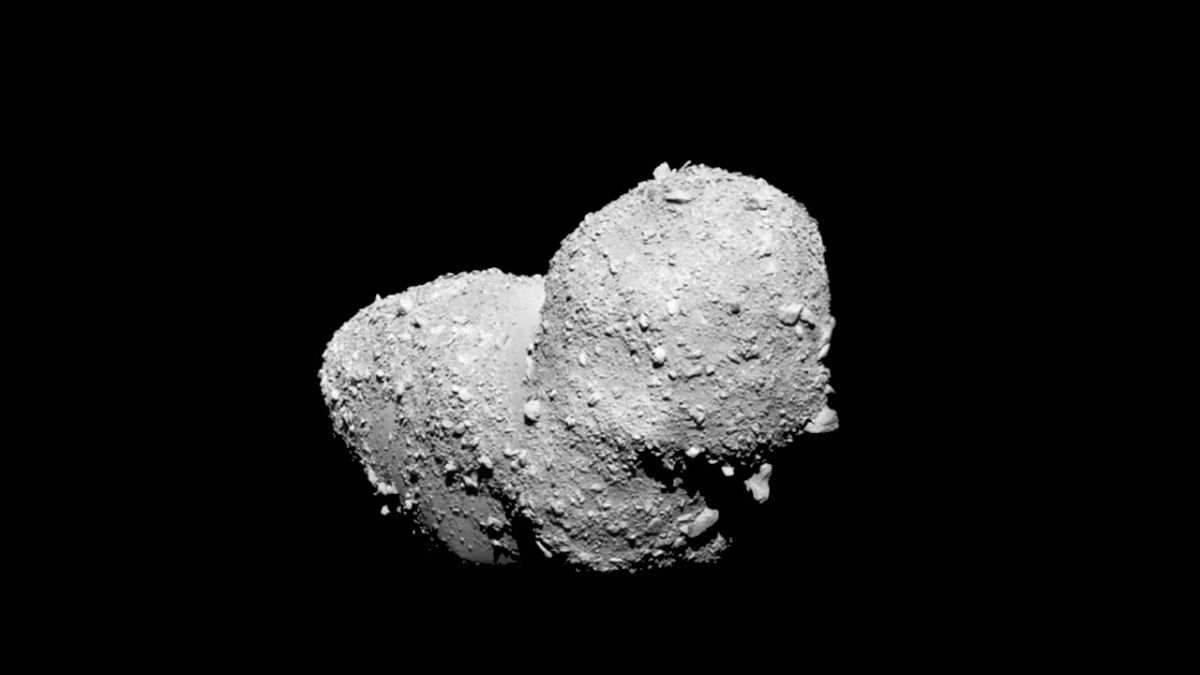

The infamous “space peanut” is aptly salty: Tiny salt crystals have been found on peanut-shaped asteroids, suggesting that the solar system’s largest space rock may be more water-rich than astronomers thought.

Sodium chloride crystals, which can only form in the presence of water, were found in samples from the asteroid Itokawa returned to Earth by Japan. Hayabusa mission in 2010.

Scientists have long theorized that asteroids were one of the primary ways in which water, an essential element of life, was delivered to the early Earth. The team that discovered the salt crystals said the discovery was interesting given that Itokawa is an “S-type” asteroid. This finding has led to a number of asteroid Its orbit around the sun isn’t as dry as scientists thought, and most of Earth’s water arrived via asteroid bombardment during Earth’s violent early history.

Related: Water found in tiny dust grains from asteroid Itokawa

“The grains are just like what you would see if you took table salt from home and put it under an electron microscope,” said Tom Zega, professor of planetary sciences at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory and lead author of the new paper. explaining the discovery name. “They’re these nice square crystals. It was fun because they were so surreal that we had a lot of lively group meeting conversations about them.”

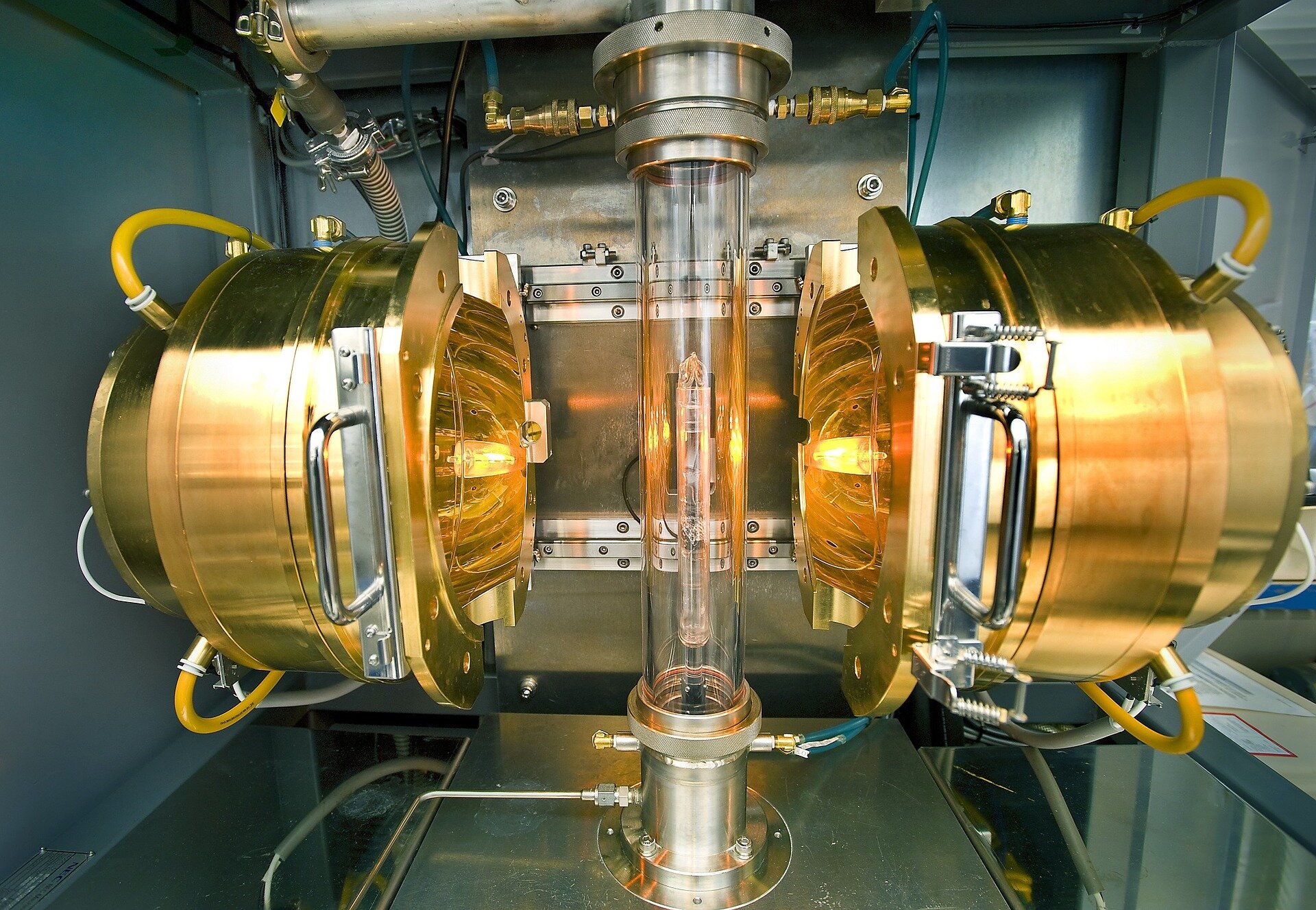

The team made the discovery by analyzing an Itokawa sample collected by Hayabusa in 2005 that was less than twice the width of a human hair. From these tiny pieces of space rock, the team extracted smaller samples about the size of yeast cells.

This is the first time researchers have confirmed the existence of salt crystals from Itokawa’s parent body, ruling out the possibility that they were the result of contamination, a problem that has plagued previous studies claiming to have found salt in a similar meteorite. birth. By comparing before-and-after images of the sample, the team ruled out the possibility that the asteroid hadn’t changed during storage and thus acquired salt during this time.

“Since the ground samples did not contain sodium chloride, we were certain that the salt in our sample came from the asteroid Itokawa,” said Shaofan Che, postdoctoral fellow at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory and lead author of the study. “We ruled out all possible sources of contamination.”

Water, water everywhere…

Itokawa’s samples represent a type of space rock called “ordinary chondrites” from S-type asteroids like Itokawa. Ordinary chondrites make up nearly 90% of meteorites found on Earth, but it is rare to find water-bearing minerals in them.

“Ordinary chondrites have long been thought to be unlikely sources of water on Earth,” Zega said. “Our discovery of sodium chloride suggests that this asteroid population may hold much more water than we thought.”

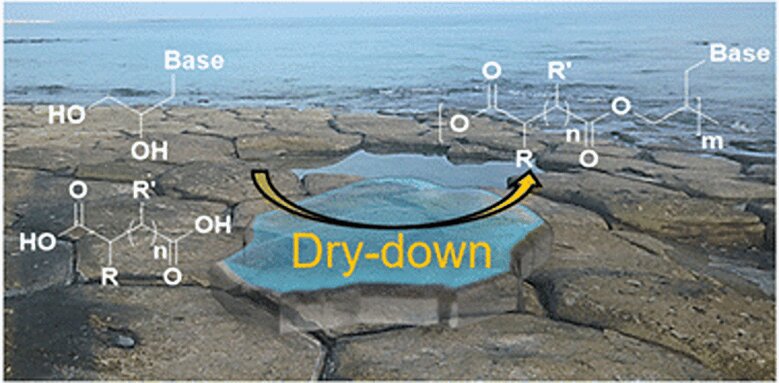

Most scientists believe that the solar nebula, a disk of gas and dust that surrounded the sun, formed about 4.5 billion years ago. solar system planets was born — the Earth was too warm to contain water vapor that could condense from the gas.

“In other words, water on Earth had to be delivered from the outer reaches of the solar nebula, where the temperature is much lower and water in the form of ice can exist,” Che said. The scenario is that a comet or another type of asteroid, known as a C-type asteroid, travels further inward from the solar nebula and impacts the young Earth, carrying its watery cargo.”

The presence of water in this other asteroid family via common chondrites means that Earth may have gotten water from a much closer location to the Sun than previously thought.

“You need a rock big enough to survive the ingress and provide water,” said Zega. “If it turns out that the most common asteroids are far more ‘wet’ than we thought, the hypothesis of asteroid watering will become more plausible.”

Did Itokawa have parents of water?

About 2,000 feet long and 750 feet wide (610 x 229 meters), Itokawa is thought to have been dislodged from its much larger parent body, and the team believes that frozen water and frozen hydrogen chloride may have accumulated in the object. naturally occurring decay of radioactive elements Researchers say the frequent bombardment by meteors during the Solar System’s violent early days on Itokawa’s parent asteroid could have provided enough heat to sustain hydrothermal processes associated with liquid water.

“When these elements come together to form asteroids, liquid water has the potential to form,” Zega said. “And once it’s in liquid form, you can think of it occupying the asteroid’s cavity and potentially having water chemistry.”

This bombardment will eventually break this larger body into smaller pieces, creating Itokawa, the team said.

Scientists found a sodium-rich silicate mineral called plagioclase in the sample, suggesting that salt crystals within Itokawa have existed since the early days of the solar system when they were part of a larger celestial body.

“When we see such altered veins in terrestrial samples, we know that they were formed by aqueous alterations, which means they must contain water,” Che said. “The fact that we see textures associated with sodium and chlorine is another strong indication that this happened on asteroids when water passed through disodium-containing silicates.”

The study is described in a paper published June 12 in the journal. natural astronomy.

#Salty #Peanut #Asteroid #Reveal #Earth #Water